Language is fundamentally important for understanding human behavior. Yet describing language in useful ways is difficult due to the complexity and size of textual data. Natural language processing (NLP), the field at the intersection of linguistics and computer science has made great progress in describing and classifying textual data. Nonetheless, applications of natural language processing with convincing causal implications are few.1

No Country for Old Members represents the cutting edge of the application of NLP to understanding human behavior.2 The paper describes how language use evolves over time on two beer rating platforms and claims to test theories of language use.

Why do we care about how language use changes over time in a community?

- The determinants of language use are important objects of theorizing in neuroscience and linguistics.

- Economic theories of institutions3 suggest that language will evolve over time to reduce transaction costs and become efficient (is this actually the case?).

- Understanding language use dynamics may be useful for designers of platforms.

The authors seek to measure the diversity of language use and the change in the type of language used per user. How to measure the diversity of language use is unclear a priori. For example, do we care about specific words, topics or sentiment? The authors choose to use measures based on specific words because they are interested in new word adoption by users. However, I can easily see a similar paper written about topics or sentiment. The main goal of the paper is to uncover how community members learn to use novel language.

The measure that the authors use for understanding the novelty of language is called cross-entropy. Cross-entropy is computed by estimating the likelihood of finding a given bi-gram in a post in each month and then applying it to out of sample posts. Higher values of their cross-entropy measure correspond to more “surprising” language used. The authors’ first result is that the cross-entropy of language decreases over time within both platforms.

At this point I want to stop and note a major difference between how an economist and a computer scientist would handle inference about cross-entropy. The authors of the paper mention no underlying model of language usage and do not compute standard errors. An economist would want to know the statistical properties of cross-entropy. My worry is that due to the fact that the cross-entropy will mechanically be higher at the beginning of the sample because there are fewer observations.

The next question that I would pose if I were writing the paper is whether the change in cross-entropy is due to:

- A change in the composition of users

- The composition of beers reviewed

- A change in the language used by user.

I would first try to answer my question by decomposing cross-entropy with a linear model with fixed effects. Then, I would write down a model in which individuals have tendencies to use certain words but can also be influenced by other visible reviews. What implications would such a model have for the joint distribution of n-grams over time?

The authors focus mostly on understanding whether the language usage choices of individuals changed over time. They claim that their evidence supports that user adopt new language during the “adolescence” of their usage on the site. The life-stage of a user is a measure of the post number compared to the last post number of a user that exists. The authors show that new users have high cross-entropy and that cross-entropy decreases initially but then increases at the end of the user-lifespan.

They then posit two competing hypotheses for the increasing distance between the user and community.

- The user stops adapting the language of the community.

- The user starts using non-standard language.

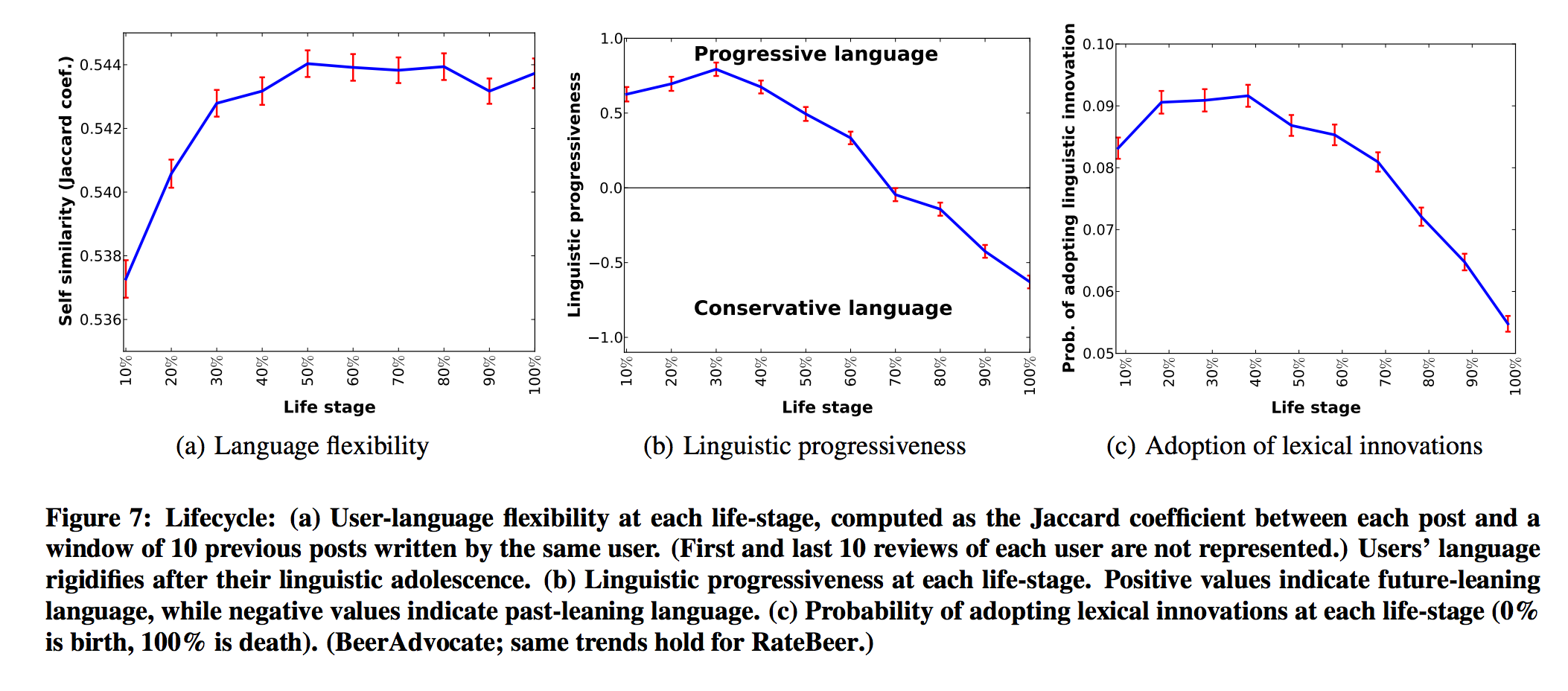

The authors use three measures of linguistic change within a user (See Figure Below). First, they use Jaccard similarity4 to show that self-similarity of language increases initially and then stabilizes. They suggest that this fact implies that the user stops adapting the language of the community. They then show that user’s language at the beginning of site entry is similar to the language used in the future of the site as opposed to the past. Lastly, they show that new users are more likely than old users to use verbal “innovations”.

The authors fail to consider the most obvious hypothesis to explain the data, that the demographics of users change over time and that different demographics use different words. The demographic hypothesis can explain the above facts because a gradual demographic change will look like an evolution of language use within the platform. On average, at the beginning of entry, a user’s demographic has not yet achieved its maximum representation in the platform. Thus, what looks like language adoption and innovation can really be the addition of similar users over time.

The Jaccard similarity of users posts is the most intriguing piece of evidence. Why do we observe that later posts are more similar to each other than earlier posts? The authors claim that later posts are more similar because users no longer adopt lingual innovations. Some other, untested, possibilities include changes in the time between which each post was written and changes in the types of beers reviewed. To flesh these possibilities out more, consider that users may initially dabble in writing reviews but as they gain experience may choose to write reviews more frequently. Reviews written closer together will be more likely to use similar language. Relatedly, it is unclear why the authors do not present any results in this section based on absolute measure of time elapsed since first post. Another explanation of the data is that after users learn what type of beers they like, they only review specific styles of beer. Reviews of similar beers will have more similar language.

A more general problem with the authors’ approach is that the distribution of beers reviewed by users changes over time both across users and within users. The authors claim to deal with changes in beers reviewed by ‘macro-averaging’. I do not understand what such a technique means in the context of which beers are reviewed. Changes in the demand for beers over time seem very difficult to account for in the context of this analysis. Perhaps a beer style by beer style computation of cross-entropy would be useful.

The final piece of the paper includes a prediction exercise in which linguistic features improve predictions of user exit. I find increased predictive accuracy uninteresting because a lot of other, correlated pieces of data such as cohort or demographics could improve predictive accuracy as well.

The authors cut up the data using an impressive assortment of techniques but they do not take the problem of causal inference seriously. Identifying the causal effects of social influence is an immensely difficult problem.5 Distinguishing between learning and time-trends is also difficult. The paper treats competing explanations of the data generating process in an ad-hoc manner, always favoring explanations based on learning and social influence.

The analysis in the paper would benefit from a formal mathematical model of linguistic choice. Without a model, I am not sure how to interpret the magnitudes described in the paper. How many specific new words were learned? Is the change in cross-entropy greater or less than expected?

In conclusion, I learned a lot techniques from this paper but not much about actual human behavior. Nonetheless, I am optimistic about the potential of applying NLP to the analysis of communication in communities.

-

A nice exception is Gentzkow and Shapiro’s paper: [What Drives Media Slant? Evidence from U.S. Daily Newspapers] (http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/matthew.gentzkow/research/biasmeas.pdf) ↩

-

“No Country for Old Members” won the best paper prize at WWW 2013. ↩

-

North, Douglass. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press, 1990. ↩

-

A measure of linguistic distance. ↩

-

Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem is a great exposition of the problems one encounters when studying social effects. ↩